Movie Review: Is Soul (2020) Soulless?

From Toy Story (1995) to The Incredibles (2004) to Up (2009), Pixar Animation Studios has become a household name by producing high-quality animated films that aren’t just for kids. In recent years, however, the Disney-owned company has drawn criticism for a perceived slip in quality of writing, with titles like Cars 3 (2017) and Incredibles 2 (2018) often cited as examples of perennial sequels straying from the heartfelt message of the original films. In any case, after four entries in the Toy Story franchise, it was encouraging to see Pixar assaying a new concept with 2020’s Soul.

Soul shares some motifs with previous Pixar hits Inside Out (2015) and Coco (2017). All three films focus on a character’s journey through a nonphysical realm and carry a strong emotional message. However, Soul is notably more surreal than either of its forebears, focusing on more abstract, intellectual, and even existential topics, such as death and fulfillment, as opposed to the simpler emotions of joy, anger, and sadness personified in Inside Out. This is reflected by the film’s cooler color palette, limned with blues and teals instead of the bright hues typical of animation. Soul‘s design choices in general are refreshing, featuring distinctive character designs and vivid backdrops evocative of the surrealist setting.

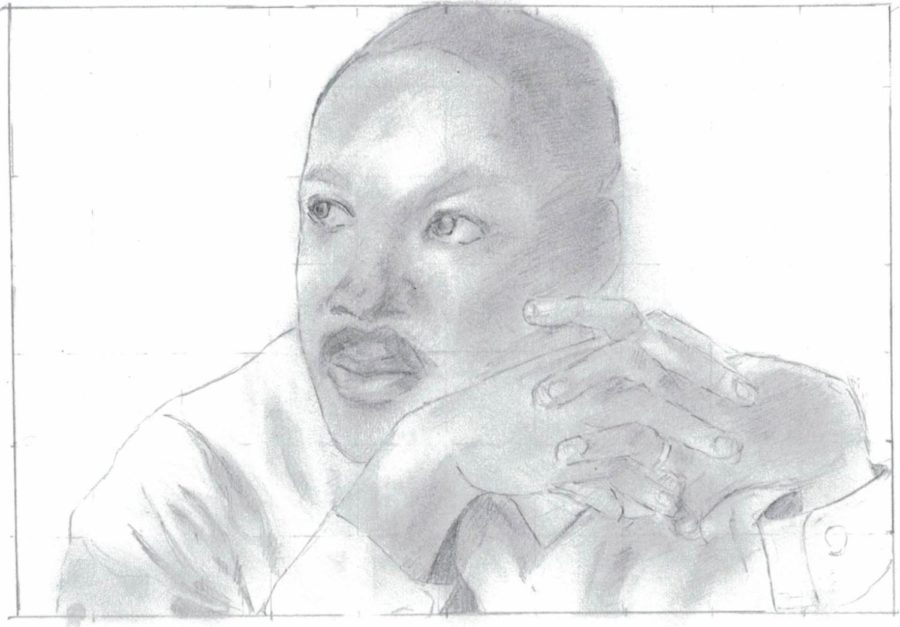

The protagonist, voiced by Jamie Foxx, is Joe Gardner (the first African American main character of a Pixar film), a music teacher with a passion for jazz whose soul moves to the Great Beyond after he falls into a manhole. Unprepared to face whatever comes next, Gardner evades death and embarks on an often reflective escapade through both the spiritual and physical worlds. Soul spends just as much of its running time on Earth as in the metaphysical plane, and the colorful scenes of Gardner in his human form often pack a firmer thematic punch. Overall, the film addresses advanced yet relatable themes in a pensive manner, sparking more critical thought than raw emotion, unlike other Pixar projects. Its unique aesthetic and moving message of introspection are delivered subtly by scenes like the barbershop and Gardner’s post-concert reflection. However, Soul is not without its foibles.

The critical problem is that while Soul boasts several powerful scenes, the plot beats connecting them are tenuous at best. Rather than flowing naturally, the film feels disjointed; the script uses bizarre excuses to move from one scene to the next, like the shaving incident. Soul also wastes far too much of its run-time expounding the rules of its universe only to disregard them at several junctures. Earlier Pixar movies, like Ratatouille (2007), simply embraced the absurdity of their plots: when Linguini asks Remy how he can control him by tugging his hair, the rat merely shrugs; without delving into any nitty-gritty details, the plot hole is closed and the audience is satisfied. In contrast, by systematizing its setting Soul tears more gashes in the narrative than it seals.

Finally, the film’s climax is inept. The emotional crux of Soul comes several minutes before the actual climax, which feels blunted and unnecessary. The script insists on having its cake and eating it, too, establishing a hero’s sacrifice only to nullify the stakes of said sacrifice moments later for a banal, happy ending.

Is Soul soulless? Not at all. The film presents a clear and compelling message. Unfortunately, it still bears the trademarks of a clunky, manufactured movie rather than a hand-woven passion project. The spark was there, but Soul‘s tremendous potential is undermined by its stilted plot and self-indulgent conclusion. Ultimately, Soul is worth watching, and is a step in the right direction for Pixar, but it lacks the robust body of the classics from the studio’s heyday.

![Senior Ditch Day... Relaxation or Truancy? [Video]](https://achsstinger.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/IMG_7119-900x599.jpg)

![Heavy Rain Hits Cam High [video]](https://achsstinger.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/maxresdefault-900x506.jpg)